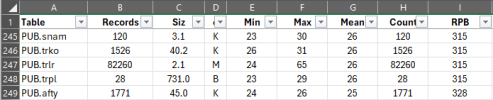

Here is a screenshot of some of our offenders:

These tables are so tiny that it isn't worth worrying about doing any tuning for them. Presumably, in this 4 GB database there are some more interesting tables? If a table is very large/fast-growing, it should have its own area. And its indexes should have their own area. Of course, there is a lot more that can be said about good structure design.

Can you post your full dbanalys report and your current and proposed structure?

Would changing RPB help? And what would be the downside of keeping 256 RPB as a "one-size-fits-all" default instead of 128?

What is "Count" in your table? The numbers are the same as the record counts. Is it record fragment count?

RPB 256 is a fine choice, in my opinion, for a multi-table area, assuming 8 KB block size. There is no penalty for not filling a record block's row directory, e.g. if some tables have larger records. In some scenarios, a higher RPB could exacerbate problems with record fragmentation, e.g. if your code creates large numbers of records and later updates/expands the records, so there isn't sufficient space in their record blocks for all of the new field data. So far, it is not clear that you need to worry about that.

I ran a tabanalys on the db and noticed that more than half of the tables have very small records, thus not filling up our 8k blocks.

Disk space is cheap and this database is small. Don't worry about tiny tables or partially-filled blocks. Some gaps are inevitable and harmless, apart from tweaking a DBA's OCD tendencies.

Change blocksize from 8K to 4K

No. 8 KB block size is more efficient.

We are in the middle of a clean-up of old data in our database, deleting approximately 25-30% of the contents.

How are you deleting data? Programmatically? If so, be sure to compact the relevant indexes afterwards, as mass data purges can hurt performance, which catches some people by surprise. Of course, you won't need to do this if you do proceed with a D&L as you will be rebuilding all of your indexes.

Our db is 4GB and buffer hits are 100% so intervention may not be needed at all.

I can't say, based on what I have seen so far. While a low buffer hit ratio is definitely bad, a high buffer hit ratio is not necessarily good. E.g.:

Code:

repeat:

for each tiny-table no-lock:

end.

end.

This will give you an excellent buffer hit ratio. That metric, by itself, doesn't mean all is well with database or application performance.

We have done a D&L a few years ago, which took us ~20 minutes.

This analysis/discussion will likely take more of your time than performing the entire D&L. So, apart from the fact that it's 20 minutes out of your free time, why not do it during your Saturday morning coffee break? As you're proposing it as an option, I assume you can afford the downtime.